In the Knapsack problem, you are given \(n\) objects each one with a given integer weight \(w_i\) and value \(v_i\). You can take a subset of these objects such that the sum of their weights is at most a given capacity value \(C\). The goal is to maximize the total value of the selected objects.

Example

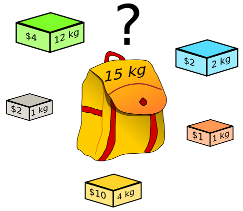

Consider the knapsack with capacity 15 and the objects shown in the following figure.

Image source: wikipedia

The optimal solution is to take all objects except the green one. The total weight is \(1 + 4 + 1 + 2 = 8 \leq 15\) and the total value is \(2 + 10 + 1 + 2 = 15\).

In order to solve this problem with dynamic programming, we first need to think about it as a sequence of choices. What are the choices we are making here?

For each object we have two options: either we take it or we don't. So far so good. The next step is to think about what information we need to keep track of in order to decide whether a choice is possible. Do we need to know what objects were taken so far?

No. The exact set of objects taken so far is too much information, all we need to know is the remaining capacity of the knapsack. If the remaining capacity is larger than or equal to the weight of the object we are deciding on, then we can take either take it or not take it. Otherwise we are forced to not take it.

Also, observe that the order in which the decisions are made does not matter. If a set of objects fits into the knapsack, it does not matter in which order you decided to put them, only the total weight matters.

This suggests that we go through the objects one by one, in the order in which they are given and for each of them make a decision. Given what we said above, this means that we need to keep track of two pieces of information:

- The index of the current object \(i\)

- The remaining capacity \(c\)

We call such a pair \((i, c)\) a state of the problem. Each state corresponds to a subproblem that we denote by \(dp(i, c)\) with the following meaning:

\(dp(i, c)\) is the maximum value we can obtain by selecting a subset of the objects \(i, i + 1, \ldots, n - 1\) from a knapsack of capacity \(c\).

The original problem is described by the state \((0, C)\) since \(dp(0, C)\) represents the maximum value we can obtain by selecting a subset of all objects on a knapsack of capacity \(C\).

The next step is to think how the subproblems relate to each other. For that we need to look at the choices that we have at each state.

- If we do not take object 0 then we need to solve the subproblem \(dp(1, C)\): what is the maximum value we can get by putting a subset of the objects \(1, 2, \ldots, n - 1\) into a knapsack of capacity \(C\)? This is because we already made a decision for object 0 and since we did not put it into the knapsack, we have the full capacity remaining for the other objects.

- If we take object 0 then we need to solve the subproblem \(dp(1, C - w_0)\): what is the maximum value that we can get by putting a subset of the objects \(1, 2, \ldots, n - 1\) into a knapsack of capacity \(C - w_0\)? This is because we put object 0 so the knapsack capacity to put the remaining objects is reduced by the weight of object 0, \(w_0\).

We can then generalize and write a recurrence relation between subproblems:

There are a couple of observations that we need to make about this recurrence.

- At some point the index of the current object will reach the value \(n\). The subproblems of the form \(dp(n, c)\) mean: what is the maximum value we can obtain from selecting a subset of objects from an empty set of objects on a knapsack of capacity \(c\). Clearly the answer in this case is 0 as there are no objects to choose from.

- At some point the knapsack capacity may become negative as the second option, taking object \(i\) is only possible if \(c - w_i \geq 0\). An easy way to overcome this is to define the value of a subproblem with negative capacity to be \(-\infty\).

With this observations, we can complete our recurrence relation:

It should be now a simple task to write a recursive function that computes this. The answer to the problem will be \(dp(0, C)\).

static int C, n;

static int[] w, v;

static double dp(int i, int c) {

if(c < 0) return Double.NEGATIVE_INFINITY;

if(i == n) return 0;

// do not take item i

double skip = dp(i + 1, c);

// take item i

double take = v[i] + dp(i + 1, c - w[i]);

// memorize the value of state (i, c)

return Math.max(skip, take);

}

The reason for using doubles here is simply because it provides a negative infinity that behaves as \(-\infty + x = -\infty\).

Now, just like this, the code still runs very slowly since for each state it will make two recursive calls. Thus, the total number of recursive calls is \(O(2^n)\).

This is easy to overcome. Look at the recursive call parameters. It is a state \((i, c)\). How many different such states exist?

The answer to this is simply the number of possible values for \(i\) times the number of possible values for \(c\), that is, \(O(n \cdot C)\). Since there are \(O(2^n)\) recursive calls and each of them corresponds to a state, if \(2^n > n \cdot C\) it must be the case that we have repeated some recursive calls. In other words, some states are uselessly computed several times.

We can avoid this repetition by storing the result of each recursive call in a table. Then, we can simply check whether the current state has already been computed and return the value that was stored previously if that is the case.

static int C, n;

static int[] w, v;

static Double[][] memo;

static double dp(int i, int c) {

if(c < 0) return Double.NEGATIVE_INFINITY;

if(i == n) return 0;

// check if the value for state (i, c) has already been computed

if(memo[i][c] != null) return memo[i][c];

// do not take item i

double skip = dp(i + 1, c);

// take item i

double take = v[i] + dp(i + 1, c - w[i]);

// memorize the value of state (i, c)

memo[i][c] = Math.max(skip, take);

return memo[i][c];

}

In this case, since each call takes constant time and each state is computed only once, the total runtime of the algorithm will be \(O(n \cdot C)\).

The matrix has size \(n \times (C + 1)\) since \(i\) can range between 0 and \(n - 1\) and \(c\) can range between 0 and \(C\). It should be initialized before calling dp as follows:

memo = new Double[n][C + 1];

INGInious

INGInious